- Home

- The College

- College History

- Vision, Mission and Motto

- Organogram

- Governing Body

- Institutional distinctiveness and Best practices

- Infrastructural Facilities

- Statutory Cells and Committees

- RTI

- Students’ Grievance Redressal Cell & Internal Complaints Committee

- AISHE

- College Office

- Teaching Staff

- Non-teaching Staff

- Code of Conduct

- Accolades

- Collaborations/MoUs

- College Alumnae

- Principal’s Desk

- Academics

- Activities

- Facilities

- Infrastrucatural Facilities

- Library

- e-library

- WEBEL

- Green Initiatives

- ICT Facility

- NCC

- NSS

- Students’ Common Room

- Common Room

- Canteen

- Hostel

- Hobby Classes

- Placement Cell

- Psychological Councelling Cell

- Electoral Literacy Club

- Film Club

- Magazine

- Women’s Study Centre

- Women’s Cell

- Legal Cell

- Research and Development Cell

- Student’s Corner

- Scholarships

- Students Council

- Alumnae

- Library Reading Room

- Hostel

- Canteen

- Sports

- Students’ Common Room

- Placement Cell

- Competitions

- Anti-Ragging Committee and Anti-Ragging Squad

- Hobby Classes

- Film Club

- Magazine

- Psychological Councelling Cell

- Electoral Literacy Club

- Consumer Club

- Women’s Cell

- Legal Cell

- Nandanik: A Centre for Performing Arts

- Equal Opportunity Cell

- Environmental Compliance Committee and Nature Club

- Admission

- Value-Added Education

- IQAC

- Placement Cell

- Library

- Open and Distance Learning

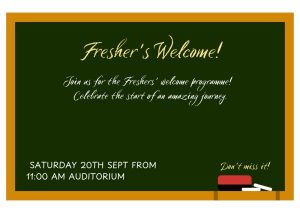

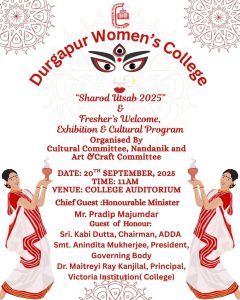

Celebrate the festive spirit at Durgapur Women’s College Sharod Utsab 2025 with fun, culture, and grand welcome!

Celebrate the festive spirit at Durgapur Women’s College Sharod Utsab 2025 with fun, culture, and grand welcome!

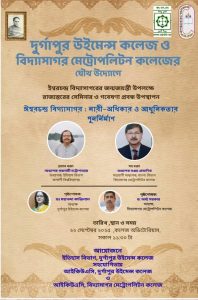

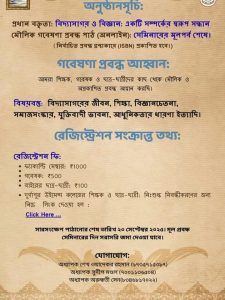

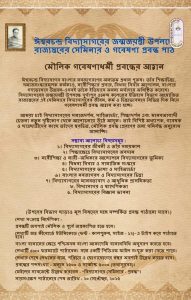

State-level Seminar on “Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar: Reconstructing Women’s Rights and Modernity” on 22nd September 2025 at Durgapur Women’s College Auditorium.

State-level Seminar on “Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar: Reconstructing Women’s Rights and Modernity” on 22nd September 2025 at Durgapur Women’s College Auditorium.

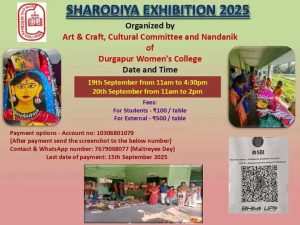

Don’t miss the Sharodiya Exhibition 2025 at Durgapur Women’s College on 19th & 20th September – a celebration of art, craft & creativity!To encourage the local women entrepreneurs and students of art and craft classes of the college , SARADIYA EXHIBITION will be held on 19th and 20th September, 2025

Don’t miss the Sharodiya Exhibition 2025 at Durgapur Women’s College on 19th & 20th September – a celebration of art, craft & creativity!To encourage the local women entrepreneurs and students of art and craft classes of the college , SARADIYA EXHIBITION will be held on 19th and 20th September, 2025

Tribute on the occasion of the 79th year of India’s Independence to the immortal revolutionaries of Bengal.

Tribute on the occasion of the 79th year of India’s Independence to the immortal revolutionaries of Bengal.

Durgapur Women’s College participated in the two-day International Seminar at NSHM, where Principal Dr. Mahananda Kanjilal was invited as a speaker and the college was felicitated.

Durgapur Women’s College participated in the two-day International Seminar at NSHM, where Principal Dr. Mahananda Kanjilal was invited as a speaker and the college was felicitated.

Sharod Utsab 2025

Sharod Utsab 2025